Survival of the Greediest

How unchecked greed and wealth worship are devouring the world — and us with it

This is my last post before I vanish for two weeks to rest, swim in the sea, read books, and wander through crumbling ruins.

But if you find yourself missing my work, The Noösphere’s archive has nearly 300 essays, some of which are free to read for all. And as usual, if you value the thinking, reading, and occasional existential spiralling that goes into this newsletter, do like or share this essay, become a paid subscriber, or buy me an (iced) coffee. Thanks so much for being here.

Erysichthon, a mythical king of Thessaly — a region in central Greece — was a man of immense wealth and power.

But one day, driven by boundless greed, he ordered his servants to cut down a grove of trees sacred to Ceres (known in Greek mythology as Demeter), the goddess of harvest, fertility, and the earth, so he could expand his home and host ever-larger feasts. When they refused to fell one particular tree, an ancient oak at the heart of the grove, Erysichthon seized an axe and did it himself, killing in the process a tree nymph who had tried to warn him of the consequences.

From that day on, the king was cursed with an insatiable, relentless hunger. No matter how much he ate, it was never enough. Nothing could satisfy him. Even after selling all of his lands and herds and properties and his own daughter, Mestra, to buy food, the hunger remained. Eventually, Erysichthon ate himself.

There are quite a few other ancient myths that warn us about the dangers of unchecked desire for material possessions and social status. And yet, humanity still fails to learn from these stories. The result? A world increasingly full of Erysichthons, stomping through life like gods and endlessly filling their plates even when they’re already overflowing.

Perhaps worst of all, many of us still don’t seem to have a problem with it — or realise just how bad it’s become.

Economic inequality is often treated as inevitable and constant. There will always be winners, we’re told, and there will always be losers. And if the present feels bleak, just imagine being a penniless peasant toiling in the pouring rain while your lord feasts on roast goose and drinks his body weight in red wine. (As if having to pee in bottles so your boss can fund yet another phallic space rocket is some grand ‘upgrade’ from those times, which weren’t even as grim as we like to believe.)

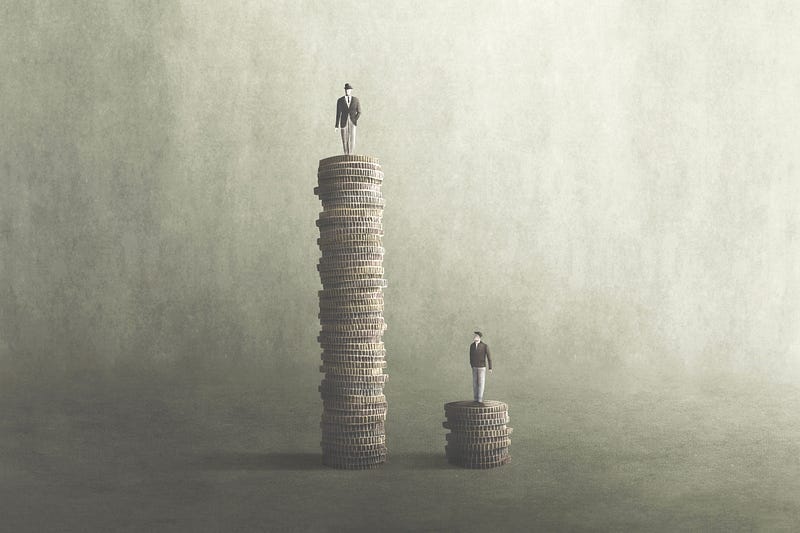

But the facts of rising income and wealth inequality — and rapidly so — are hard to ignore. And few economic measures capture it quite as starkly as the yawning gap between CEO and worker pay.

It wasn’t always so bad, though. In the 1970s, CEOs in the US typically earned around 20 to 30 times the average pay of their company’s workers, according to estimates from the Economic Policy Institute (EPI). By the 1980s, the ratio had climbed to around 60-to-1, already raising alarms for some. As economist Peter Drucker wrote in 1986:

Few people — and probably no one outside the executive suite — see much reason for these very large executive compensations. There is little correlation between them and company performance.

But if earning 60 times the average employee’s pay was already considered ‘very large,’ then what language is left to describe what came next? By 2000, the CEO-to-worker pay ratio had exploded to 372 to 1. And by 2021, it climbed even higher — to nearly 400 to 1, the highest ever recorded. Overall, realised CEO compensation grew by 1,460% between 1978 and 2022, far outpacing both S&P stock market growth and the earnings growth of the top 0.1%. What was once — and not that long ago — widely viewed as excessive is now business as usual at many big companies.

And in some cases, it’s not just excessive — it’s outright absurd.

A 2022 report by the Institute for Policy Studies found that at America’s low-wage companies, CEOs now earn, on average, 670 times more than their workers. At some firms, the gap is even more staggering, with CEO-to-worker pay ratios exceeding 1,000-to-1. In other countries, these disparities tend to be lower, but they’re far from what could be considered reasonable. In the UK, for instance, some FTSE 350 companies report ratios as high as 2,820 to 1. Still, if you look at the highest-paid top executives in the US corporate world, things are getting increasingly bonkers, too. In 2023, several American corporations paid their CEOs thousands of times more than what their average employees earned. Abercrombie & Fitch, for example, reported a CEO-to-worker pay ratio of 6,076-to-1. Meanwhile, Mattel clocked in at 3,620-to-1.

To put that into perspective: if the average employee wanted to earn what Abercrombie & Fitch CEO Fran Horowitz makes over a seven-year CEO tenure (the average for S&P 500 companies), they’d have to work for… 42,000 years. That’s essentially the span of time between the first cave paintings and today. (It’s also not lost on me that while women are still rare on top-paid CEO lists, the person with the most obscene ratio is indeed a woman. Yet another reminder that ‘girlboss feminism’ isn’t liberation — it’s the same oppressive structures, only with a different face.)

Still, today’s top executives don’t just collect big, fat paychecks. They frequently pocket generous stock and options grants, too. A new, more transparent measure of executive earnings, known as Compensation Actually Paid (CAP), factors that in, and, unsurprisingly, it paints an even more astronomical picture of CEO pay. According to this measure, the largest annual pay package ever recorded was awarded just last year: $6.8 billion to Alex Karp, CEO of defence and tech firm Palantir. And while some might argue that because this is largely tied up in stock, it doesn’t really ‘count,’ it’s worth keeping in mind that, in the same year, Karp sold $2 billion worth of stock to cash in on the high market value.

How long would it take an average Palantir worker to earn that much? I was going to spare you the math, but, well, I couldn’t help myself — you’d have to work more than 56,000 years to earn what Karp made in just one year. And if you earn an average wage, even longer than that.

It’s really not surprising that we’re on track to have the world’s first trillionaire in a few years from now. What a time to be alive.

I wonder how many people truly grasp just how much a trillion is. (That’s one thousand billion.) Honestly, even a billion — one thousand million — can be hard to wrap your head around, let alone imagine a single human owning that much. Yet today, thousands of individuals hold billions, over a dozen sit on fortunes of hundreds of billions, and with each passing year, those numbers continue to rise. In 2024 alone, the world churned out four new billionaires every week.

And while it’s difficult to say for certain how this compares to the wealth concentration of the past — simply because we lack good data — it does seem like the Overton Window on what counts as an ‘acceptable’ level of pay disparity and economic inequality has shifted quite a bit. Accumulation of excessive wealth, once viewed as avarice or even a deadly sin, now seems mostly accepted, even admired, and any critique of it is too often dismissed as jealousy or bitterness. Why does it bother you if other people are more successful? Why should it matter how many zeros someone has in their bank account?

Well, it should matter to all of us. Because the problem isn’t just that our world is crawling with Erysichthons.

It’s that we’re all living in Demeter’s sacred grove. That is: Earth.

The meteoric rise in CEO compensation over the past few decades hasn’t happened in a vacuum. It’s been aided and abetted by several forces — including deregulation, financialisation, weakened labour protections, etc., all of which allowed large corporations and executives to get richer and richer at the direct expense of working people. As a result, while CEO pay skyrocketed — by a staggering 1,460% between the late 1970s and today, as I mentioned earlier — the average worker’s wages barely budged. According to the EPI, they grew just 18.1% in the same period.

Still, in many places, including the US, the UK, and across the European Union, rising wages are hardly keeping up with rising prices. Even when commodity costs fall, consumer prices only continue to climb — and so, too, does CEO pay. We’re clearly being squeezed harder and harder, with 71% of the world’s population now living in places where inequality is on the rise while those at the top keep padding their fortunes. Pointing this out isn’t envy. It’s common sense.

The resulting extreme economic gaps drive other problems, too, such as poor health outcomes, erosion of public trust, democratic decay, and the rise of anti-social behaviour. The roots of wars and conflicts — which reached their highest global peak since World War II last year, by the way — lie in inequality as well. But also, in greed. Because what is war, really, if not the ultimate expression of greed, of insatiable hunger for land and resources and power and domination, no matter the cost in human lives?

Greed never exists on its own. It brings with it death and destruction — including of our environment. After all, endless growth always demands sacrifice. And more often than not, that sacrifice is a piece of our planet. Our sacred grove.

Unfortunately, we don’t seem to have any goddesses watching over us, no nymphs to curse those who take far more than they need. Or if they do exist, they’ve been gagged by the sheer force of billionaire capital. Because that kind of money doesn’t just buy stock portfolios, real estate, or megayachts — it buys influence to rewrite the rules of the game to serve its own interests, creating the perfect conditions for greed to spread even further. Just like an infectious disease would.

In a recent speech, economist Ha-Joon Chang observed:

Economics is now playing the role of Catholic theology in Medieval Europe. It has become an ideology that tells people that the world is what it is because it has to be, however unjust, wasteful and inefficient it may look.

Chan then points to a core contradiction at the heart of market capitalism: according to the market, the very people who make our world go round — healthcare workers, teachers, farmers, etc. — are worth very little. Those who engage in care work, child-rearing, and domestic labour — mostly women and girls — are valued even less; often, not at all. Meanwhile, those perched atop the largest corporations are deemed practically priceless.

But which group could society actually not survive without? Who is truly indispensable to a flourishing world? And what, exactly, is the real function of those we technically value most?

Back in the times of peasants and lords, the latter at least had to fulfil some form of social duty and allow the public to use their private resources when needed, as economic historian Guido Alfani notes in As Gods Among Men. Today, they instead use their considerable political and financial influence to shirk even that minimal responsibility. There’s also no proof that a growing number of billionaires benefits society in any way. (Actually, there’s increasing proof that it doesn’t.) They’re not necessarily the smartest, most talented, or most innovative among us either. They are just the greediest. Or, in some cases, luckiest.

The same goes for many executives. While they may be held accountable for their company’s profits, those profits aren’t generated by their labour alone. They’re made possible — overwhelmingly — by the workers. And it’s the fruits of their effort that we eat and wear and drive and use and rely on every single day. If CEOs were paid drastically less — or better yet if there were a legal cap on their compensation — nothing fundamental about our daily lives would worsen. In fact, you could argue things might even improve since workers would finally receive a fairer, more livable share of the pie they baked.

The case for other reforms, especially tax reforms, has never been stronger than it is today, either. It’s been estimated, for instance, that taxing billionaires worldwide at just 2% of their net worth could raise around $250 billion a year. That’s roughly ten times what’s needed to end extreme hunger. And sure, while it might not be easy to tax the bulk of the assets or net worth of wealthy individuals, since much of it’s ‘stored’ in companies, trusts, and other structures or entities, complexity shouldn’t be an excuse for inaction.

Even partial taxation is better than sitting idle while inequality grows more and more grotesque by the day.

It’s worth remembering that greed hasn’t always been humanity’s Achilles’ heel, even if it might feel like it sometimes now. The values that become central to our systems and stories can always be changed.

But if we’re not careful, and we wait too long to change them, it won’t be us ‘eating the rich.’ They’ll eat our world, then us, and then probably themselves, too. Because the old myths were right: greed is boundless.

And no matter how many forests the ultra-wealthy tear down for their feasts, their hunger will only grow.

Of a monster no longer a man. And so,

At last, the inevitable.

He began to savage his own limbs.

And there, at a final feast, devoured himself.

— Erysichthon, from Ted Hughes’ ‘Tales from Ovid’

Excellent post!

Thank you for your excellent research and your cogent writing. Why do these evil greedy people want more and more and more? I don't get it. You can't eat more than four meals a day. I wish there was some way to stop these people.