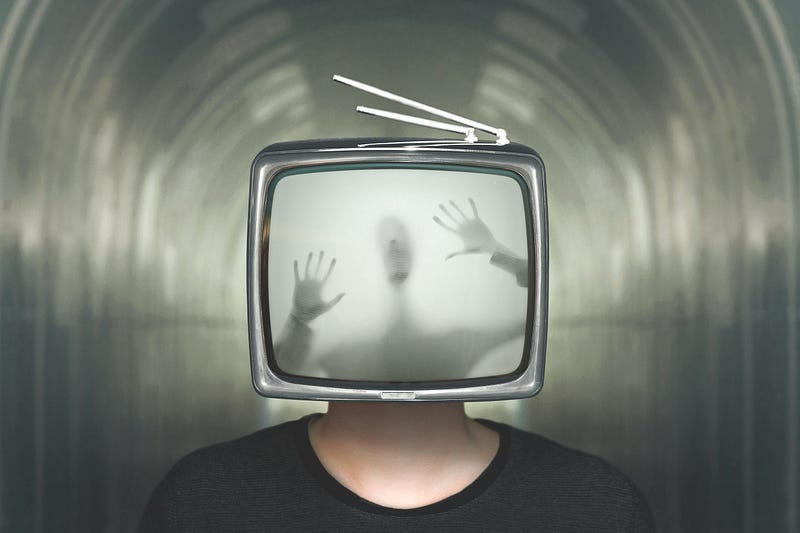

The Scariest Thing About the Misinformation Epidemic? No One Is Immune to It.

Yes, that includes you and me as well

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Noösphere to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.