Why Young Men Think That When Women Gain, They Must Lose?

On the rise of zero-sum thinking about gender equality and how it’s harming everyone

The Noösphere is an entirely reader-supported publication that brings the latest social sciences research into frequently overlooked topics. If you read it every week and value the labour that goes into it, consider sharing this essay or becoming a paid subscriber! You can also buy me a coffee instead.

The recent gains of far-right parties in the EU elections, last month’s Republican National Convention in the US, and the ongoing extremist riots in Britain share one striking commonality: a strong turnout of young men.

Meanwhile, young women are increasingly gravitating in the opposite direction, becoming arguably the most progressive generation in history.

Earlier this year, a major Gallup poll published by the Financial Times painted a similar picture: globally, young women are becoming more liberal, while young men either stand still or actively shift to the right — including the far right. But this growing ideological gender gap shouldn’t really be surprising to anyone following politics lately.

In Germany, far-right politicians are explicitly targeting young men with messages like ‘real men stand on the far-right,’ promising that this is ‘the way to find a girlfriend.’ Meanwhile, in the US, disaffected young men and a specific brand of manhood — loud, fist-pumping, and domineering — have taken centre stage in the Republican Party’s current campaign. This was on full display when former President Donald Trump entered the stage at the Republican National Convention to the tune of the 1966 hit song, ‘It’s A Man’s Man’s Man’s World’.

It’s clearly a calculated move on the part of right-wing politicians, online pundits and the so-called ‘manfluencers’ to target young men and boys, capitalising on their frustration, anger, and dating woes and then lure them in with the promise of a return to a ‘man’s world’ — a dream that, naturally, hinges on the good, old-fashioned subjugation of women.

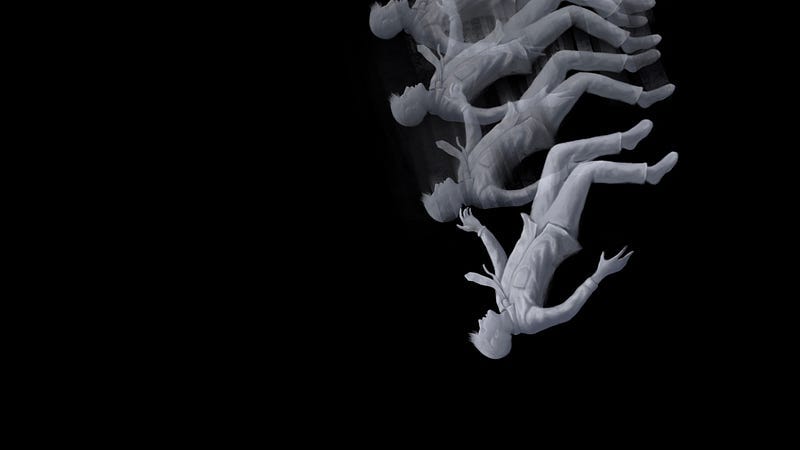

Through this lens, women’s improving status in society and feminism are also seen as the root causes of young men’s struggles today. If women are gaining, then men must be losing, the logic goes.

But is this zero-sum narrative a fair description of what’s really happening?

One of the most alarming aspects of this recent shift of young men towards the right is the accompanying rise in misogynistic rhetoric. According to a recent study in the UK, one in five (21%) men aged 16 to 29 have a favourable view of Andrew Tate, who has infamously claimed that ‘women belong at home’ and are ‘men’s property.’

This is also reflected in surveys showing that young men are increasingly rejecting women’s rights and feminism, asserting that it has ‘gone too far’ and ‘makes it hard for them to succeed.’ In the UK, half of men between the ages of 16 and 24 share this belief. Meanwhile, in the US, most (60%) Gen Z men think the country has become ‘too soft and feminine,’ according to research by political scientist Melissa Deckman.

It’s hard not to wonder: what exactly have women done to provoke such a backlash from men?

You’d think we suddenly started committing most acts of violence against men, pushed them out of schools, the workplace and government, and enacted laws to keep it that way. But that’s not the case, is it? Violence — and the threat of it — remains largely a male domain, and men still hold most leadership positions as well as decision-making power in this world.

Nevertheless, it’s true that women are slowly — though peacefully — catching up. Today, more girls graduate high school than boys, with OECD countries having an average graduation rate of 86% for girls compared to 79% for boys. Girls are more likely to pursue and complete higher education, too. In the US, for every 100 bachelor’s degrees awarded to women, men receive only about 74. Even in traditionally ‘masculine’ academic fields like medicine, there are now more women enrolled than men. In some big cities, young women even outearn their male counterparts, while female breadwinners are steadily on the rise. Young women also often flee the nest much earlier than young men.

It might be tempting to conclude, well, women are indeed advancing while men are falling behind. Our world no longer holds women back through a combination of legal restrictions, educational barriers, and cultural norms (or, at least, not as explicitly as it used to), and men are struggling to adapt.

Sociologist Michael Kimmel terms this phenomenon ‘aggrieved entitlement’ — a sense of anger and fear felt by men, particularly white men, as a result of losing their perceived social status and privilege. This is also well-documented in psychological research. When high-status groups — such as men — see lower-status groups — women — gaining power and resources, they often feel threatened. The perception that discrimination against the lower-status group is decreasing can also lead the higher-status group to fear that they will face more discrimination instead.

It’s like when someone says, ‘hey, we should all have a slice of this pie,’ and suddenly the guy who’s been eating the whole pie starts worrying there won’t be enough left for him. Perhaps he won’t even get a crumb now.

Women’s increasing participation in the workforce, educational attainment and, consequently, financial independence also put a dent in the ‘man the provider’ model, which remains a cornerstone of ‘traditional’ masculinity. And when men feel unable to fulfil this role or that they must compete with both men and women to do so, it can lead not only to aggrieved entitlement but perhaps apathy, too. Deckman’s research into Gen Z political motivation reveals that while young men lean more right, they also care significantly less than their female counterparts about most issues — including economic ones, typically considered more important to men — and, overwhelmingly, don’t feel motivated to act at all.

Then there’s also what seems to be a Cold War era in heterosexual relationships. Many young women, disillusioned by the relationships their mothers and grandmothers endured, are becoming more selective — or opting out of dating altogether — since they no longer need marriage for financial security. Meanwhile, some young men take women denying ‘access’ to them as an unthinkable affront, further inflamed by conservatives’ claims that this would never happen in a ‘man’s world.’

If our world were a pie, it seems men are getting — or choosing to get — an increasingly smaller share of it. How true is that, though?

Gloria Steinem famously said:

We’ve begun to raise daughters more like sons, but few have the courage to raise our sons more like our daughters.

I often wonder how much of some men’s anger stems precisely from being raised without being encouraged to embrace a much bigger human canvas, perhaps even expecting a world that no longer exists. And then, when trying to replicate the lives of their fathers or grandfathers inevitably fails, they blame society — and women — for it.

Of course, all of this can and does harm men, too. Men’s struggles in today’s world, including young men’s, shouldn’t be dismissed or ignored.

Still, I take issue with the narrative that young women — or women in general — are ‘taking over’ and thriving at the expense of young men. In fact, if you look at more than just a few social indicators, the key takeaway is that, well, it sucks to be a young person today, regardless of your gender.

Issues like unemployment and loneliness, frequently framed as exclusively male problems, impact both young men and women nearly equally. Recent global studies show that loneliness is much more widespread among younger people today, particularly those aged 18 to 24, than any other age group and that it’s hardly a gendered phenomenon. Gen Z has also been hit hard by unemployment, with their unemployment rates nearly double those of older working-age counterparts in almost every OECD country. This doesn’t differ much between genders, either, but it does often affect young people of colour, LGBTQ+ individuals and those with lower levels of educational attainment more.

In many societies, young people have also been disproportionately pummeled by rising prices and higher housing costs, leading to low homeownership rates and more overall debt, particularly credit card debt and student loans.

Even in areas where young women seem to be ‘winning,’ the situation isn’t so rosy upon closer inspection. While Gen Z women might graduate at higher rates than Gen Z men, they still, on average, earn only 92% of what their male counterparts do. They may also be more likely to move out of their parents’ homes but are simultaneously less likely to own property than young men. Even the rise in female breadwinners or female doctors is a double-edged sword. For women, breadwinning doesn’t typically reduce the burden of domestic and care labour — it just means they bring home the bacon and then have to cook it, too — while the increase of female workforce in a previously male-dominated field often results in the median wages dropping.

(In fact, in countries like the UK, we’ve already seen a decline in junior doctors’ pay in recent years, which, coincidentally or not, comes at a time when there are more female junior doctors than ever.)

It’s naive to deny that women are still hindered by the leftovers of our deeply patriarchal past, just as it’s unrealistic to claim that men face no problems today. Neither young men nor women have a monopoly on struggling. But the fact that many of us do, and likely in greater numbers than previous generations, has awfully a lot to do with the fact that the pie we can bite our teeth into has shrunk significantly.

Gender equality isn’t a zero-sum game, but our current economic system sure feels like one. If it weren’t, the world’s wealthiest five men wouldn’t have more than doubled their fortunes since 2020, while nearly five billion people worldwide have become poorer, but, as a recent Oxfam report suggests, they did. We’ve created a system that disproportionately rewards a lucky few at the expense of unlucky billions, underfunds social security, health and infrastructure, and puts the very planet we live on at risk.

Anger is a perfectly rational response to this reality.

We just need to be careful not to misdirect it.

There’s a real danger in allowing the narrative that equality is a zero-sum game to spread like wildfire. Not only because it threatens to erode women’s rights (which should be reason enough) but also because of the damage it could do to our world — and men.

Yes, the loss of women’s rights is a loss for men, too. And so is the loss of our progress towards gender equality.

Although we’re still far from truly reaching it, there’s already compelling evidence that greater participation of women in various spheres of our world leads to more transparent governance, less corruption, higher community well-being, and lower poverty rates. Gender equality also contributes to longer life expectancy for both women and men, better overall health outcomes as well as healthier and happier relationships. If we continue striving for equality, I’m confident we will uncover even more benefits for everyone.

But if we don’t, and if we continue losing young men to apathy, hate and far-right extremism, everyone will suffer as a result. The version of masculinity being sold by the conservative crowd today demands that men bury themselves deeper and deeper within the patriarchy-capitalism grind, disregarding their feelings, their well-being, and often, their fellow human beings. And with men on perpetual offence, women will have no other choice than to be on the perpetual defence.

The massive collective threats we face require collective action, but the latter becomes near-impossible when we’re too busy fighting one another. What happens then when we fail to find common ground where it’s really needed?

Of course, it’s important to recognise and address issues disproportionately affecting women and men, but we must also listen to one another and then look beyond gender. Too often, women only discuss women’s issues and gender equality in rooms full of women, while men only discuss theirs when trying to hijack those conversations or in the dark corners of the internet.

The way forward is to acknowledge what we all stand to lose if we don’t work together and what we all can gain if we do.

This is also in line with psychological research on intergroup relations: bringing opposing sides to talk on equal footing, focusing on commonalities and creating shared objectives reduces animosity and the ‘us vs. them’ mentality that so often triggers zero-sum thinking.

Let’s not forget, though, that we’re only caught in an increasingly inhuman competition for resources that are actually abundant by choice, not necessity. But this cycle doesn’t need to continue.

And women and men need not ‘battle’ for power.

To paraphrase Mary Wollstonecraft, women don’t wish to have power over men but themselves. It’s a shame that this fundamental idea behind the women’s rights movement and modern feminism is so often forgotten.

In the end, most of us rise and fall together.

And there’s enough of the ‘pie’ for everyone.

We just need to realise that there is, and that equality is not a loss for men but a gain for humanity.

I may be wrong about this – it’s been years since I was a student – but I have the very strong impression, rightly or wrongly, that a great many policies to address historical discrimination against women have had negative effects for young men, men who had nothing to do with that discrimination and feel (rightly or wrongly, again) that they are being discriminated against because they’re men.

This leads to a curious paradox. Seen from above, men wield most of the power; seen from the POV of Joe Bloggs, a 15-year-old student in high school, men are facing discrimination. He is told that men have all the power, but his lived experiences don’t bear that out. He feels powerless and poor – the idea he is actually rich and powerful is a sick joke. To him, his teachers are (at best) wrong and (at worst) openly lying. Once he gets the idea the teachers are lying about one thing, it’s a short hop to believing they’re lying about everything.

It gets worse when he goes for a job. It may be a decent response to historical discrimination to give women an edge, but from Joe’s POV – again – the playing field is tilted against him … and he needs that job. It is not in his self-interest to sacrifice his own career to help another, particularly when his lived experiences suggest woman are not suffering from any discrimination. He may be wrong about that, too, but his lived experience disagrees.

Put crudely, when Alan and Alice raced, Alice had a ball and chain attached to her ankle and had to work twice as hard to get half as far. This was blatantly unfair, and so when Ben and Bella raced the chain was removed; Ben still won. This also seemed unfair, so Charlie got the ankle chain when he was racing Catherine and (of course) lost.

Why would Charlie be happy about losing, under such circumstances? How fair is it to blame Charlie for Alan having such a huge advantage … and why is Alan still allowed to claim victory, when he had that advantage?

The thing is, you cannot resolve historical discrimination by engaging – intentionally or not – in present discrimination. That just stores up trouble for the future.

I’m a Gen x woman. My sons are in college. Without question, their female peers carry around a narrative that utterly blows my mind. They believe they are still suffering under the patriarchy. Girls, the patriarchy hasn’t been a thing since well before I was an undergrad in the 90’s. Every single one of my female friends are the breadwinners in their households - all

advanced degrees. There were literally zero impediments put in place for their life paths. Female hiring quotas affected both my brother’s and husband’s chances at their respective jobs their first go round and that again was the 90’s. It’s not misogyny from zero sum thinking, they are just up to their eyeballs hearing about how oppressed women are when none of the data bear this out.