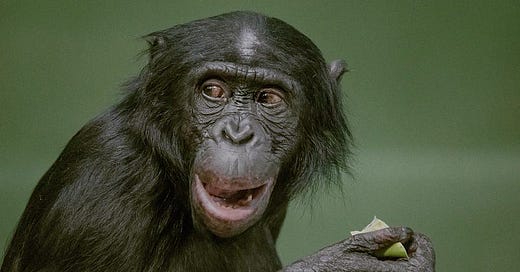

Want To Topple the Patriarchy? Learn From Female Bonobos.

These matriarchal apes can teach us a thing or two about power, alliances, and keeping the peace

The Noösphere is an entirely reader-supported publication that brings social sciences research into frequently overlooked topics. If you read it every week and value the labour that goes into it, consider liking or sharing this essay or becoming a paid subscriber! You can also buy me a coffee instead.

Until not that long ago, female-dominated primate species were dismissed as mere ‘outliers’ and often overlooked and understudied.

The unspoken logic seemed to be: the less we examine exceptions to male dominance, the more universal and inevitable it appears. Male-dominated species, by contrast, were closely scrutinised and their behaviour amplified, sometimes even misrepresented, to reinforce existing assumptions about human hierarchies. (See: the Monkey Hill exhibit at the London Zoo.)

But today, we do know that the animal kingdom, and primates in particular, display far more social diversity than once acknowledged. (Surprise, surprise.) Recent estimates suggest that in around 42% of both living and extinct primate species, females either dominate males or hold equal social status. And this pattern appears across all major primate groups, from lesser apes like gibbons to great apes like bonobos.

The latter, who, along with chimpanzees, are our closest living relatives, are especially fascinating. Yet just as primate matriarchies were long ignored, so too were the mechanisms that sustain them — how female bonobos form, wield, and maintain power remained poorly understood, at least until very recently.

And what we’re learning now not only tells us more about them.

It may hold some important lessons for us, humans, too.

In bonobos, as in humans and several other animal species (though not the majority, as was once assumed), males tend to be larger than females. This phenomenon is known as male-biased sexual dimorphism. But in both bonobos and humans, the size difference is relatively modest and far less pronounced than in species like gorillas or orangutans.

Still, despite this difference — and contrary to traditional, male-centred explanations of sexual dimorphism — it’s not the males who call the shots in bonobo societies. Instead, it’s their smaller female counterparts. And here’s another twist — they don’t do it alone.

Most of us are probably best familiar with a top-down model of power — one individual at the top, often ruling with an iron fist (or at least a loud enough voice). That’s certainly how things work among chimpanzees, where dominance hierarchies are steep, aggressive, and typically led by males. High-ranking chimps then maintain control through intimidation and physical strength or by forging alliances and dispensing favours.

But Bonobos flip the script. Power in their societies isn’t concentrated in a single chest-thumping alpha but instead shared among a coalition of three to five females, often older and unrelated.

A recent study published in Communications Biology offers the most detailed insight yet into how these coalitions actually function. Drawing on nearly three decades of data from six wild bonobo communities in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, it confirmed what some have suspected for decades: female bonobos use strong social bonds as a behavioural tool, not just to suppress aggression, but to catapult themselves into positions of influence. The researchers dubbed it the ‘female coalition hypothesis.’

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the vast majority (85%) of observed cases of female coalitionary aggression were directed at males who stepped out of line, whether by harassing a female or her offspring or trying to monopolise food. And in 61% of those conflicts, the females came out on top. Defeated males typically lost social rank and sometimes sustained injuries — in the most extreme cases, even death — while their female opponents gained status. Interestingly, some males joined these female-led ‘gangs,’ too.

The study also confirmed that female bonobos usually occupy the highest ranks in their communities, with an average female outranking about 70% of the males. Still, this varied quite a bit across different groups and periods. In the Eyengo and Kokoalongo communities, for instance, females were almost never outranked by males and rarely lost conflicts with them. In contrast, in the Ekalakala community, the average female outranked only about a third of the males. The key difference? In the first two groups, females consistently supported one another, which helped them win conflicts and advance through the ranks.

As Martin Surbeck, a behavioural ecologist at Harvard University and lead author of the study, explains:

We have found what everybody already knows — that when you work together, you’re more successful and you gain power. (…) In bonobo communities, females have a lot to say. And that’s very different from chimpanzee communities where all adult males outrank all females in the group, and where sexually attractive females receive a lot of aggression by the males.

Previous studies have also noted that bonobos have lower overall levels of fighting and wounding — earning them the nickname ‘hippie chimps’ — as well as reduced male competition for access to females compared to other apes. (A recent study did claim that bonobos are far more violent than chimpanzees, but that conclusion was based on the behaviour of… twelve bonobos. And all of them were male.) Even inter-group conflict seems rare. In one experiment at Wamba, Japanese primatologist Takayoshi Kano placed sugarcane bait right on the boundary between two bonobo communities. If these had been chimpanzees, it would have ended in a bloodbath. But instead, it sparked a love fest — while the males kept their distance, the females crossed group lines to engage in sexual interactions with other females and occasionally with a few males, too.

Bonobos are also the only non-human species observed to practice a form of ape ‘midwifery,’ with female birth attendants assisting the labouring mother, grooming her, and standing guard.

Most likely, none of this would be possible without the tight-knit, interdependent social networks that female bonobos form — webs of cooperation, solidarity, and shared power.

But humans might have had those once upon a time as well.

It’s worth noting that, just as in the past or surviving female-centred human communities, female-led structures in the animal kingdom — also seen in species like lemurs, vervet monkeys, geladas, hyenas, killer whales, lions, spotted hyenas, and elephants to name a few — aren’t simply mirror images of male-dominated ones. Females aren’t necessarily clashing antlers over male attention, staging violent power grabs, or taking over typically ‘male’ roles; they’re often working from an entirely different script.

Among vervet monkeys, for example, female leadership initially went unnoticed because it’s distributed among multiple females, frequently older, who position themselves in the middle or rear of the group, unlike the males at the front, who were once mistakenly assumed to be in charge. Still, decision-making usually relies on group consensus.

Among elephants, although the matriarch — typically the oldest female — ultimately has the final say, she usually solicits suggestions and considers the well-being of the entire herd before making decisions.

But cooperative behaviour and tight coalitions aren’t exclusive to female-dominated animals either. Even in bonobos’ sister species, chimpanzees, females occasionally form small, durable coalitions — often for self-defence or to protect vital resources. It’s also not uncommon for both females and lower-ranking males to join forces and overthrow a male leader when he becomes too despotic, violent, or cruel.

Anthropologist Christopher Boehm, who spent decades observing primates and studying different human cultures, argued that this practice of collective subordinate rebellion isn’t just a quirk of nature and likely played a role in early human societies as well. It’s also the foundation of his ‘reverse dominance hierarchy’ theory, which proposes that these societies weren’t ruled from the top down but from the bottom up — like an upside-down pyramid — with everyday people banding together to stop anyone from rising too far above the rest. This, Boehm suggests, is what made egalitarianism among hunter-gatherer communities both possible and sustainable. As he puts it:

By my definition, egalitarian society is the product of a large, well-united coalition of subordinates who assertively deny political power to the would-be alphas in their group.

Recent data from our closest relatives, the bonobos, provides support for this idea, too. And so does evidence from egalitarian and female-centred human societies, which are frequently oriented around need rather than dominance and where collective welfare and consensus outweigh individual power. It’s then likely that for millions of years, humans and our ancestors relied on tight-knit coalitions and collective decision-making to maintain social harmony, resolve conflicts, protect resources, and keep would-be tyrants or particularly violent or disruptive individuals in check.

Could it also be that it was mostly female coalitions holding the line in those early days of humanity? Perhaps. In Eve: How the Female Body Drove 200 Million Years of Human Evolution, scholar Cat Bohannon argues that the survival of early humans likely depended on both the existence of a highly cooperative culture and the presence of strong female coalitions. As she writes:

(…) cooperative culture bad to come before monogamy started. You had to have other cultural checks in place before measures to create paternal certainty made sense. You had to have bands of ancient hominins who were interdependent and had created clear and dire consequences for any behaviour that threatened children.

What you basically needed was a matriarchy.

But as humans began organising into patrilocal systems, where women left their kin to join their husbands’ families, these tight female bonds naturally began to fray. They weakened even further with the rise of patrilineality, where property and status passed through the male line, reinforcing tighter male coalitions. And again, during the brutal witch trials, when women’s gatherings, support networks, and knowledge-sharing were cast as suspicious, dangerous, and even ‘demonic.’

And as those female social networks were continually and systematically undermined, so too was the collective power they once held.

It’s unfortunate that, in the human jungle, women and girls are still taught to see each other as rivals — for male affection, for approval, for limited seats at the table — instead of allies and sources of strength.

Meanwhile, female sociality continues to be trivialised, dismissed as idle gossip, emotional excess, or a distraction from Actually Serious Matters.

Studies, too, suggest that women sometimes intentionally distance themselves from other women or become more critical of them, a phenomenon known as the ‘queen bee’ effect. But this happens mostly just in male-dominated, sexist environments, where opportunities for women to advance are limited, and where they might feel the need to align with dominant, traditionally ‘male’ norms. In more gender-equal or women-led spaces, the pattern reverses: collaboration rises, competition wanes.

But, alas, those kinds of environments — whether in the world of work or beyond — are still far too rare, aren’t they?

And while we’re busy picking each other apart, policing one another’s choices, and hoping that conforming to patriarchal expectations might earn us a leg up, the system behind this circus keeps happily humming along, mostly rewarding those it’s always valued more anyway. It’s really about time we understood that division and isolation are simply tools of control, trapping us in a scarcity mindset that makes scrambling for scraps feel desirable and normal when it absolutely isn’t.

Our power lies, just as it always has, in sticking together. And so, what we truly need to topple the patriarchy — and every other system of inequality — isn’t just a handful of superheroes (or supershe-roes) swooping in to save the day. As inspiring as some high-profile individuals can be — at least those who don’t only care about lifting themselves — lasting change rarely comes from the top down or from one person at a time. It takes collective action, shared responsibility, and everyday people showing up for one another, again and again. And not only women.

Issues like male violence — long at the top of the feminist agenda — don’t just harm a staggering number of women and children worldwide. They harm men, too. Restrictions and biases that continue to limit half the world’s population in education, employment, and leadership also don’t just hold women back — they hold entire societies back, including the men in them. Not to mention the toll the rigid gender hierarchies upholding them take on men’s well-being.

It’s in everyone’s interest to stand up to bullies, tyrants, aggressors, and those who profit from sowing division, whether along lines of gender, race, class, ethnicity, or any other identity. But it doesn’t take everyone. Just enough of us. And it doesn’t require bold, lone acts of heroism. The power of crowds doesn’t lie in spectacle — it lies in sustained, collective defiance. In being active bystanders in the world we live in.

Just like our bonobo cousins.

While it’s important not to draw overly simplistic parallels between animal behaviour and human society, bonobos, with whom we share nearly 99% of our DNA, can give us valuable clues about where we came from. But they can also point to possibilities — including for our future — we might otherwise fail to see.

Too often, we look at the world and at what’s possible to build within it through such a painfully narrow lens. We get stuck on ‘biological inevitabilities’ and the excuse that ‘this is how it’s always been,’ slamming the door shut on imagination before it even gets a foot in.

Let’s not forget that another thing we share with bonobos — and with many other primates — is a remarkable capacity for innovation and adaptability.

The human world has never stood still.

And there’s no reason it should start now.

I love this. People think science and scientists are "liberal" or "progressive" but the biggest and most important bias in science is status-quo bias.

Completely agree that it’s in everyone’s interest to defeat "bullies, tyrants, aggressors, and those who profit from sowing division, whether along lines of gender, race, class, ethnicity, or any other identity."

But I'm currently writing about how it's actually not in most men's best interest to stand up to bullies. Unless you're strong and powerful enough, or have enough men behind you who are, the bully is just going to beat you up, or kill you.

Agree it doesn’t take everyone. But it does require a critical mass. Asking individual men to just reject patriarchy, just perform femininity, without acknowledging the risks and costs to them of doing so, has not been and likely will not be a winning formula.

Wow. Thank you 😊.

What an incredible piece of riveting reading. It's so refreshing to be offered a little bit of hope like this, especially to those of us who have become very cynical and wonder if men will ever seek to grow. Let's learn from the wise creatures of this beautiful planet and intentionally support other women wherever we can.

I love your writing so much.